LIST OF WRITERS

Artspace K

Serenity • Hong Kong – Wong Hau Kwei Ink Art Exhibition

Exhibition Period: 21 July – 23 October 2022

Artist: Wong Hau Kwei

Writer: Hayley Wu

Serenity • Hong Kong – Wong Hau Kwei Ink Art Exhibition

“It doesn’t matter if you use avant-garde, traditional or western style; the most important thing is to convey the timely significance of the era.” – Wong Hau Kwei

The coronavirus pandemic these two years has casted a shadow of anxiety over Hong Kong. Artspace K is pleased to present “Serenity • Hong Kong”, a solo exhibition of works by prominent contemporary artist Wong Hau Kwei depicting urban and landscape images in Hong Kong. We hope our exhibition will convey a renewed sense of peace and calm.

Wong’s works blend traditional Chinese ink painting techniques and modern western aesthetics. Accentuating the contrast between black and white, opacity and luminosity in the expression of light and color, Wong establishes a distinct style that transcends ink art to a different level. By sharing his portrayals through brushstrokes and ink to reflect the atmosphere of the time, we hope that visitors can experience the unique qualities of Hong Kong.

Writer – Hayley Wu

(Connected via HKAGA Summer Programme 2022 Open Call)

Hayley Wu is a cultural worker and writer based in Hong Kong. Their work is interested in networks of solidarity, popular media in digital and localised spaces, and ideas of the urban and the rural. Previous works have appeared in Sine Theta Magazine, the Liminal Review, Rulerless and Fringe of Colour.

For more details, please visit gallery’s website here.

Wong Hau Kwei’s ink paintings show the enduring qualities of Hong Kong’s landscapes

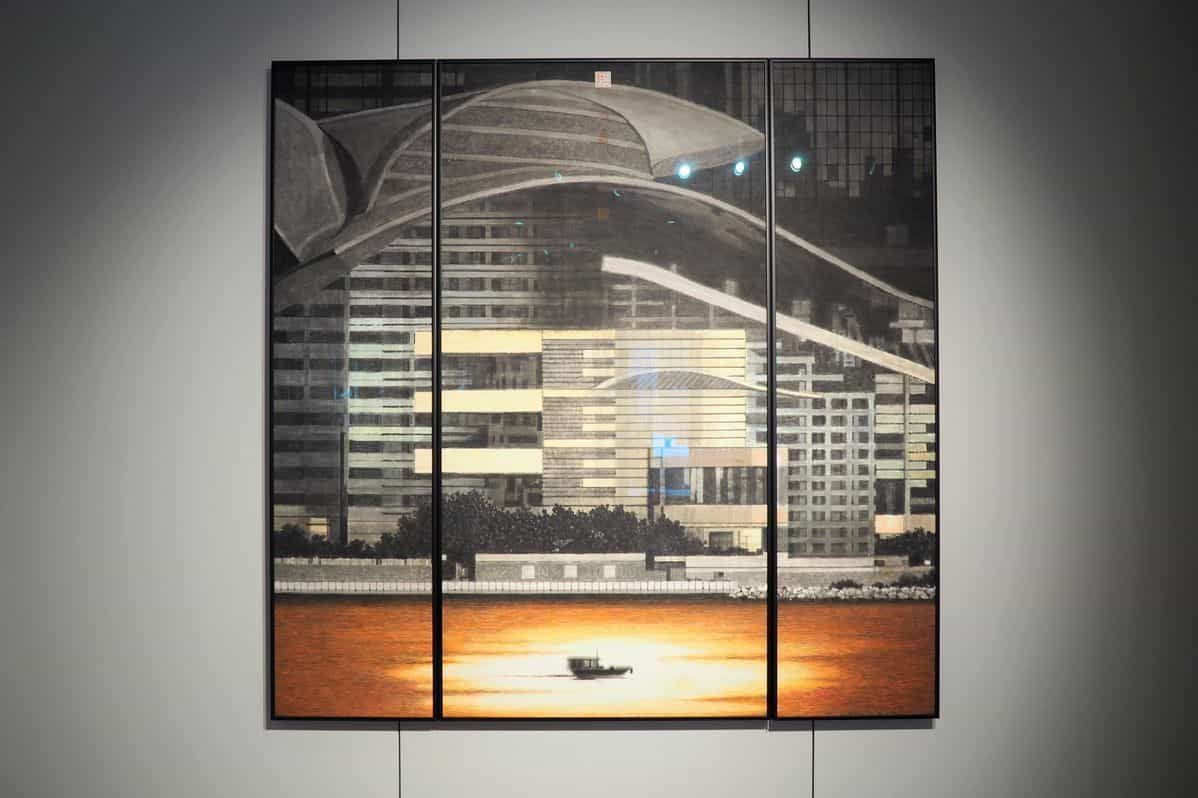

A solo exhibition of ink paintings by artist Wong Hau Kwei, “Serenity • Hong Kong” is an exploration of the city’s urban and natural landscapes. Presented at Artspace K, these glimmering works capture a peaceful, subdued version of Hong Kong, in sharp contrast to its reputation as a bustling international hub. The works, made from 2009 to 2022, depict a range of locations: iconic landmarks of the city, scenes from daily urban life, as well as images of nature in and around Wong’s home in Clearwater Bay and beyond. Through his use of light and shadow, Wong’s paintings capture these landscapes in moments of transition; yeet the body of work comes together to present the enduring qualities of Hong Kong, amidst constant change.

The choice to feature a large proportion of works set by Hong Kong’s seascapes seems fitting, given Artspace K’s location in Repulse Bay. Travelling to the gallery is an exercise in drifting away from the frenetic energy of the city’s urban centre, as one moves through the southern coast of Hong Kong Island. The journey to the gallery is marked by scenes of sunlight glimmering against the gentle waves of the sea; a visual motif that recurs across Wong’s works, such as in the case of Glistening Light on Water, or Shadow of Clouds. In these works, the artist alternates between long and short dashes of ink to create the effect of light fragmenting upon bodies of water. Wong generates a sense of calm amidst movement through his careful attention to detail in his ink paintings of the sea, producing a sense of continuity between the natural landscape just outside of the gallery and the interiors of the exhibition space.

Interspersed between Wong’s paintings of the natural landscapes are more familiar scenes of Hong Kong’s urban and residential spaces. What creates a sense of visual harmony across his work is the continual and restrained use of colour, limited to shades of black, white, red, orange and yellow. Wong seems particularly interested in drawing attention to the subtle shifts in light across surfaces, and the gradations of colour across a given landscape. This manifests itself most dramatically in Hoping, which depicts the sea on the brink of daybreak. A glimmer of the rising sun sits at the horizon point of the scene, resulting in a vibrant splash of light in the sky, which is then reflected in more diffuse tones across the calm morning sea. At the same time, vertical bars of gray score the sea’s surface, as the clouds in the sky interrupt the vibrancy of the morning light. A similar interest in the gradations of light is seen within an urban context in Good Morning Hong Kong, which teeters between the shadowed lines of the city’s buildings still in slumber, and the bright luminescence of morning light hitting against its windowed surfaces.

While the treatment of light is consistent across Wong’s paintings, there are marked differences in the textures of his works when representing natural and urban landscapes. Lion Rock captures the monumentous scale of the famed mountain through its use of blank space. A haze of clouds takes up a large proportion of the triptych, Lion’s Rock peaking out only across the top third of the work. The craggy surface of the mountain and the gradual change in opacity as the clouds take over the iconic location stand in stark contrast to sharp lines in Twilight at Victoria Harbour, which displays the sloping yet crisp lines of the Hong Kong Convention Centre. Here, the change in light through colour sits within the frames of each panel of glass, highlighting the angularity of the city’s architecture. The difference between Wong’s treatment of natural and built space is apparent within Twilight at Victoria Harbour itself, as diffused light frames a singular boat travelling through Victoria Harbour at the bottom of the painting.

Other features play into the idiosyncratic visual language of Wong Hau Kwei’s paintings. A key element at play is the interest in scale and a sense of open space through constraining the proportions of his works, seen in the use of narrow, horizonal canvases for works such as the ones in the Clear Water Abode Series. The breadth of these paintings, often featuring solitary sailing boats and a narrow stream of movement behind them, emphasises the expanse of nature and the sea in these scenes. Vertical space is similarly used in the Sketch of Clear Water Abode series. Even with his smaller works, such as Morning or Village House, Wong gives space to the clouds above the residential houses which form the subjects of these paintings. Open space is thus a key motif in the artist’s works. Another key feature of Wong’s works is his use of traditional seals as part of the work. While seals are traditionally used in place of a signature, in the artist’s works they often incorporate additional messages. Moreover, such as in the case of the Sketch of Water Abode series, Wong often features them prominently in the centre of his works, making them a centre point from which the rest of the landscape eminates.

Through these paintings of Hong Kong, Wong Hau Kwei represents his personal relationship with the city and the symbols it is understood by. This intervention of the personal, alongside the use of urban elements and incorporation of Western watercolour techniques in his work, are ways in which Wong’s works can be understood as conversant with the wider traditions of the New Ink Painting Movement. The New Ink Painting Movement, pioneered by Liu Shou Kwan in the 1970s, was part of the economic and cultural period of transition in the region during that time and was one of the means by which a new Hong Kong identity was formed. Thus Wong Hau Kwei’s works might also be understood as part of this articulation of what Hong Kongness means in this contemporary moment; a sentiment reflected in his insistence that “It doesn’t matter if [a work uses] avant-garde, traditional or western style; the most important thing is to convey the timely significance of the era.”

– by Hayley Wu

Artspace K

Serenity • Hong Kong – Wong Hau Kwei Ink Art Exhibition

Exhibition Period: 21 July – 23 October 2022

Artist: Wong Hau Kwei

Writer: Hayley Wu

Essay

Hanart TZ Gallery

Nothin’ Like the Taste of Print

An Exhibition of Works by 21 Hong Kong Printmakers

Exhibition Period: 18 June – 27 August 2022

Artists: Michelle Fung, Jay Lau, Li Ning, Chivas Leung, Nicolas Ho, Justin Larkin, Erika Shiba, Kylie Chung, AnGee Chan, David Jasper Wong, Vincent Wong, Marion Decroocq, Aki Sung Oi Yau, Glary Wu, Jeannie Wong, Lau Hong Lam, Lam Lok San, Chan Yi Ting, Glo Chan, Yue Yuen Yu and Cheung Tsz Ki

Writer: Jacky Wong

(Please refer to Chinese version for writer’s essay.)

Nothin’ Like the Taste of Print

An Exhibition of Works by 21 Hong Kong Printmakers

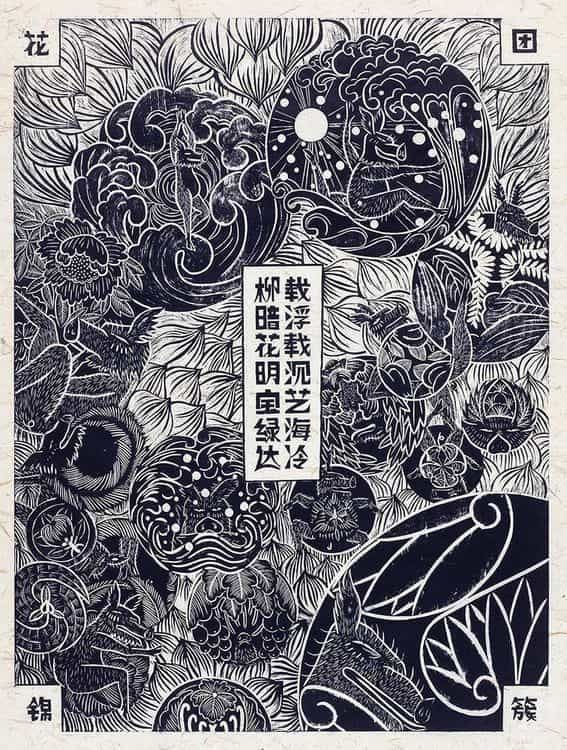

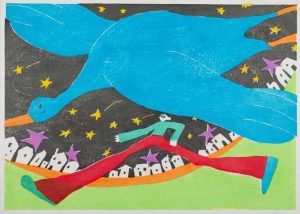

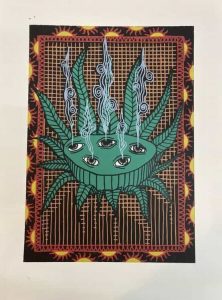

Hanart TZ Gallery, in collaboration with the Hongkong-based printmaking studio MablePrintClay, is proud to present the group exhibition Nothin’ Like the Taste of Print, shining a light on 21 up-and-coming Hong Kong printmakers.

Hong Kong has a strong tradition of printmaking. Interest in the medium has grown exponentially among both artists and collectors over the last decade, and the medium is celebrated in the form of international conferences and private biennials. The efforts of legendary artist-educators such as John Li Tung-Keung, Jane Liu, and Chung Tai Fu, have inspired a whole new generation of printmakers. One of these is David Jasper WONG, the founder of MarblePrintClay. Since its establishment in 2014, the studio has served as a hub for the local printmaking art scene. Apart from their reputation as Hong Kong’s top commercial fine art print studio, MarblePrintClay is dedicated to nurturing younger printmakers by organizing workshops and offering professional artistic support. Although the featured artists were trained at a number of different art schools and have a diverse range of styles, they all have been part of the MarblePrintClay community at different points in their careers. In a sense, this exhibition offers a panoramic view of the ongoing renascence of the Hong Kong printmaking scene.

Writer – Jacky Wong

(Connected via HKAGA Summer Programme 2022 Open Call)

Jacky Wong is one of the most active art critics in Hong Kong, with his personal column ‘HKMetropolisgallery’ on StandNews, inmedia and different social media. He shares with the readers about recent years’ Hong Kong art exhibitions, covering different generations’ streams of art. ‘HKMetropolisgallery’ is also the media partner of ArtPower Hong Kong.

For more details, please visit gallery’s website here.

Hanart TZ Gallery

Nothin’ Like the Taste of Print

An Exhibition of Works by 21 Hong Kong Printmakers

Exhibition Period: 18 June – 27 August 2022

Artists: Michelle Fung, Jay Lau, Li Ning, Chivas Leung, Nicolas Ho, Justin Larkin, Erika Shiba, Kylie Chung, AnGee Chan, David Jasper Wong, Vincent Wong, Marion Decroocq, Aki Sung Oi Yau, Glary Wu, Jeannie Wong, Lau Hong Lam, Lam Lok San, Chan Yi Ting, Glo Chan, Yue Yuen Yu and Cheung Tsz Ki

Writer: Jacky Wong

Essay (Available in Chinese only)

Denny Demin Gallery Hong Kong

The Wild and The Tame

Exhibition Period: 11 June – 3 September 2022

Artists: Jessie Edelman, L , Natalie Lo Lai Lai, Dana Sherwood, Greer Howland Smith, Paula Wilson

Writers: Harmony Chan, Hayley Wu

The Wild and The Tame

The relationship between humans and nature becomes increasingly poignant as we find ourselves en-trenched in the age of extreme human impact on the Earth. Whilst the negative connotations of this periodare apparent through climate change and the widespread impacts of human intervention, we rely on themagic and connection to the wild for restorative energy much in the same way we look to art.The Wild andthe Tameat Denny Dimin Hong Kong is a group exhibition with six artists who, through their work, observenature, creating new lines of inquiry into human interaction with the natural world.

Writer – Harmony Chan

(Connected via HKAGA Summer Programme 2022 Open Call)

Graduating from Chinese University of Hong Kong with background in Cultural Management and Art, she worked in the art industry like many of the others. Seven years serving as an art docent, enlightened her passion for art interpretation. While many thinks that docent is a retired leisure, she believes interpretation, discussion and sharing are crucial parts in the habitat which is lacking of. The pandemic hit motivated the start of the new journey in art writing, using words on paper, instead of verbally, to continue the conversation between artists and audiences. Participated in Hong Kong Visual Art Critic Nurturing Programme. Her writings have been published on The Stand News, 1a space and CINEZEN.

Writer – Hayley Wu

(Connected via HKAGA Summer Programme 2022 Open Call)

Hayley Wu is a cultural worker and writer based in Hong Kong. Their work is interested in networks of solidarity, popular media in digital and localised spaces, and ideas of the urban and the rural. Previous works have appeared in Sine Theta Magazine, the Liminal Review, Rulerless and Fringe of Colour.

For more details, please visit gallery’s website here.

Natalie Lo Lai Lai Interviewed by Hayley Wu Courtesy the Hong Kong Art Gallery Association

Natalie Lo Lai Lai (b. 1983, Hong Kong) has a distinct practice, using video installation as a means to interact with nature. She is a member of Sangwoodgoon, a farming collective started in 2010 by activists in Hong Kong who opposed the construction of a high-speed railway which would displace villagers and farmland. Lo’s practice is at once deeply connected to Sangwoodgoon while working beyond its context, using farming to think through alternatives to repressive governance and the relationships between people and nature.

Voices from Nowhere (2018) is a video piece inspired by a coincidental encounter with a farmed fishpond in Yuen Long, Hong Kong. In July 2022, we were lucky enough to get a chance to visit Tai Sang Wai and Sangwoodgoon with Lo, and to speak to her about her practice, her participation in The Wild and the Tame, and reflections on Voices from Nowhere four years on.

Hayley Wu: The Wild and the Tame marks your first time showing Denny Dimin Gallery. How did you become involved in this exhibition, and what is the connection between your work and its theme?

Natalie Lo Lai Lai: The line-up to The Wild and the Tame was made by my good artist friend Ip Wai Lung, whose work has been exhibited at Denny Dimin Gallery [in New York and in Hong Kong]. He connected me with Katie Alice, who is a partner of the gallery, and Katie Alice kindly invited me to join the group show. It was my pleasure to be invited to take part in the exhibition, which offers a platform for our six artists to address human interaction with nature through our personal experience and our works.

Voices from Nowhere responds to the exhibition’s theme by illustrating how humans curate and make a living with tamed nature–fishponds. There is no judgement on the practice, and I believe visual artists are working better to arouse contemplation on ecological issues, but not propaganda. The essay film centres my thoughts and questions on the life and death of fish, the ethics–if any–of food consumption, and so on. I am also happy and surprised that the legend and myths mentioned in the film echoes Dana Sherwood’s style of magical realism, portraying contact between human and non-human animals.

HW: Let’s go back to your beginnings. You studied fine arts, but worked as a travel journalist before becoming a professional artist. Could you tell me about that trajectory, and what you took from the experience?

NLLL: When I graduated from university, I thought, “Well, I want to make art, but just being an artist is quite boring.” So I deliberately looked for non-art jobs, like in research, and it just so happened that a journalist hired me. I worked full-time for four years, until the anti-Hong Kong Express Rail Link movement started.

That period trained my ability to look at photography. My job was to write, but with the help of fellow photographers, I learnt about what made a good photograph and what was ordinary. There were also some lines of thinking and ideas that were established during that time. While I did shoot stuff during that period, they don’t particularly show up in my works.

HW: Where can you see the influences of that time in your work?

NLLL: In the way I combine footage from abroad and from Hong Kong. My early essay films involved footage from abroad from research trips while doing my MFA, or from summer school. I didn’t want to keep the ideas in my works trapped within the context of Hong Kong, because when we talk about nature, there are actually things in common across the world. I can be a bit picky with regards to these positionings. Or with my short film, Cold Fire, the text and some of its scenes came from my thoughts on flying as a travel journalist. The concrete content of my works and my ways of thinking have both been affected.

HW: You’ve previously expressed that you’re a little uncomfortable identifying with the label ‘artist-farmer’. Why do you feel this way, and how might you characterise what you do?

NLLL: I think the honest way of describing the situation is that I have a kind of hesitancy towards what people call me or what I call myself. If I am an artist farmer, when I farm, do I keep an artist’s ego while working? I don’t want that. But to call myself a farmer is not quite right, either. Still, my art is all about agriculture. The more accurate way of describing what I do is that I vacillate between these two identities of artist and farmer, so it’s hard to label, but my practice is about farming and nature.

HW: Given that your artistic practice is so intertwined with your work on the farm, what then is the relationship between these two parts of your life?

NLLL: It must be understood as complimentary, and while my work relates to farming, it is never just about farming. My work uses farming to discuss a collective’s workload, or to understand a very different perspective towards nature. If in the past you might have thought that permaculture or organic farming was unconditionally good, then the actual practice of farming makes you recognise that solely using such methods creates another set of problems. As a farmer, you become a frontline worker who faces these issues.

Perhaps something I appreciate now that I farm is that there is no one who has the moral high ground. There are many things I understand now through the lens of human nature. I see all this through farming–which is not really just about farming–and in turn this deeply influences my artist practice and perspective.

HW: Your work addresses major political events in Hong Kong such as the 2014 and 2019 protests in Hong Kong, which largely take place in the city’s urban centres. Yet you are often responding from a rural context. How do you make sense of these seemingly discontinuous locales?

NLLL: At its core, it’s a question of how we engage with a society, a city, or a rural village under different circumstances. So an early example can be found with the Choi Yuen Village (菜園村) protests, where my collective was entering from a so-called city context into a rural village, learning about the situation– and actually, it wasn’t clear at the time why we felt compelled to protect the village. It wasn’t as if we were from there. But we slowly came to understand that these explorations of autonomy helped to override the uncomfortable feelings of living within a system. Of course, you can’t escape it. You’re still physically in Hong Kong, still paying your electricity and water bills. Hong Kong is very condensed. You can travel to the city very quickly. It’s almost impossible to separate the urban from the rural. You can try, but there is so much activity and interaction between the two contexts.

With The Days before the Silent Spring, I wasn’t trying to force the connections between the urban and rural in the work. Rather, it reflected our collective’s considerations at the time: do we stay and work on the farm, or do we take to the streets? Some members wondered if we should stay with our farm because that was what we had chosen to do. This didn’t come from feelings of apathy towards society, but rather a sense that what was happening on the farm was the best contribution the collective could offer, and that we should keep going in that direction. Whereas others thought that, in such a burning moment, what the movement needed was for people to show up. And since the collective isn’t interested in turning away from the world, we will always have these thoughts and struggles.

HW: Fermentation is a recurring motif for you, and at times it seems to be a metaphor to describe the other processes in your works. Why are you interested in fermentation, and what does it offer you in terms of thinking about humans and the environment?

NLLL: There are a few ways of looking at it. Fermenting food is something that farmers already do with leftover and unsold vegetables. It is a way of preserving and adding layers of flavour to food. But when I went to investigate and learn more about the topic, I discovered that the world and interpersonal relationships can also be understood in terms of fermentation. No matter how you try to control it, it’s hard to control. This is especially the case with wild fermentation, where its many influential factors make it hard to repeat the results.

That’s why I think fermentation is particularly appropriate for the circumstances I depict, where there are many things that can’t be controlled. Works like Cold Fire, Seesaw, The Days Before Silent Spring do this. The Days Before the Silent Spring captures the fermentation of our collective’s members over a period of time, whereas Cold Fire describes a flight journey, which is really about how to expect the unexpected, or how to prepare for emergencies. It was made during the 2019 social movement in Hong Kong. The feeling it was trying to capture was that of not knowing what was going to happen. You might also describe these works as trying to depict situations in which you have to accept the reality whether you win or lose, or in which there is no such thing as winning or losing.

HW: Can you tell us a bit about Tai Sang Wai, the village where Voices from Nowhere was shot?

NLLL: An earlier generation came down from Panyu (番禺) and first settled as rice farmers–in particular red rice, since Tai Sang Wai is in brackish water. They sold some of it, kept the rest for themselves, and after a period of time they began to build their own fish ponds. Then there was a land development project called Fairview Park (錦綉花園) in the original village. Luckily, the area was seen to have preservation value, so the developers couldn’t develop it all. The 1980s was also a time of less aggressive levels of land development, as at the time the British Hong Kong government had no interest in linking their infrastructure with Mainland China.

What is special about Tai Sang Wai is that you can see the world of the fishermen and the farmers, and how the preservation value of its natural environment protected the villagers from eviction until Fairview Park. And I’ve said recently, people are now “in relationship with air-conditioning”, and so there are always also ways in which we are disturbing the environment. Tai Sang Wai is an ideal case for describing all these kinds of relationships. Of course, its natural environment is also beautiful.

HW: Voices from Nowhere is a follow-up work to Voices from Elsewhere, a film made for the 2018 Sustainable Festival. How did this festival come about, and how did it ultimately result in Voices from Elsewhere?

NLLL: The festival started around 2017, when Art Together and the Hong Kong Bird Watching Society decided to host it together. The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society had a member called Christina who had been working on nature education. She felt that one of the poor practices surrounding nature education in Hong Kong was that educators typically just asked students to collect data, which didn’t really create a connection with nature.

As someone who enjoyed land art, Christina sought out Clara from Art Together, and proposed that they organise an event together about exploring nature in Hong Kong. There was an existing relationship between Tai Sang Wai and the Bird Watching Society, so of course they wanted to promote the fish farms.

The project recruited a few artists, myself amongst them. At the time I knew I was going to film a video work, but I didn’t want to just accept the viewpoint in which the fish farms were presented as unconditionally good. After getting to know the villagers for a while they started to tell me stories from their decades in the village, and I wanted to put these stories into my work to offer some context to the site.

With Voices from Elsewhere, it felt like no matter what I was shot I couldn’t get what I needed, and it was only in the last week that it exploded into its final form. After the festival, the Bird Watching Society allowed me to join their workshops and the villagers were kind enough to keep chatting, so Voices from Nowhere thus had more time to develop. What resulted is a work which thinks about life and death through the perspective of the fish, or about people in relation to fish.

HW: One thing I noticed about Voices from Nowhere is that its subjects seem quite un-self conscious. How did you create this effect?

NLLL: I think the feeling of “naturalness” came from my original intention to avoid directly shooting people, as in a documentary. So when conducting interviews or listening to stories from the villagers of Tai Sang Wai, I would only ever record the sound. So after we were acquainted for a while the villagers became more natural on-screen, and I think the camera angle I shot at also had an impact. The first shot of Voices from Nowhere, where a villager is pulling up the net, was just shot with a GoPro. Even though she knew she was being filmed, there wasn’t any particular pressure on her to act.

Perhaps it’s because when filming on my farm or for other works, I find it hard to avoid making people aware of the fact that they are being shot. I don’t want to seem like I’m attacking or unintentionally violating my subjects. I’ll often use more ‘relaxed’ angles to film, or use a phone, which can be easier, or shoot using lower angles where I can film people working in a more natural way. This is related to what I am filming, and the relationships I have with my subjects. I can’t film talking heads, because I find even such a simple act to be really insincere. It makes me really uncomfortable.

HW: Voices from Nowhere is an essay film, a genre you often use for your works. Why do you prefer this genre?

NLLL: I haven’t edited films for a long time; it was only from 2015, 2016 that I started making more video works. Around that time, a friend pointed out that aside from creating video installations, the way a video was cut and edited was also crucial. If a video work is good independently, it offers something different in terms of articulating a filmmaker’s thoughts. So my first video work was Glacier, and as I hadn’t had much experience with video works, it meant that I could try many things from there.

Even with simple elements such as text, visual and audio, I find there are many ways of combining them and experimenting with them. So with Voices from Nowhere, why did I stay in the village after the festival to continue learning about the fish farm? That was because for the festival, I tried to make a work that was easier to understand That became Voices from Elsewhere, which resembles a mockumentary. But I also wanted to try to make a work that centred the fish, and focused more on internal thought processes. That’s how Voices from Nowhere came to be.

One of the reasons Voices from Nowhere needs to be in conversation with Voices from Elsewhere is that aside from differences in context, they use some of the same footage. I was experimenting with how to use the same material, but to narrate a different story through text or script, and to create a completely different tone or vibe. I quite like to try these kinds of things.

HW: It’s been four years since you made Voices from Nowhere. Given that exhibiting this work again at Denny Dimin Gallery gives you a chance to reflect on the work, have there been any developments on the ideas you were trying to express then?

NLLL: For Voices from Nowhere, which was about in-depth internal thoughts, I came to feel that people are an overriding force. There is a question of rights with regards to fish farming, but the fish and plants are also working hard to survive. They’re following the course of nature, and have to face the consequences of the changing weather or risk dying out. Their lives feel a bit more timeless; they are not so concerned with questions of development. Of course, they may get wiped out by the conditions around them, but it seems that there is something more universal about their existence.

Of course, fish farmers and fishing in Hong Kong is increasingly rare, and a lot of people wonder if it is ethical. But sometimes I wonder if fish farming provides an alternative to enjoying fish? How do people arrive at these ethical positions; how does a farmer decide to grow vegetables? Why don’t we just live nomadically, picking vegetables from wild growth? Fish farming isn’t particularly bad, but it seems to be deeply affected by the changing environment. So it seems to be disappearing, and while it’s not like it can’t be protected, the practice may not be able to survive in this particular place. I’m not so pessimistic to say that the practice must be lost or will definitely disappear. I just think its only option is to find another way to survive.

In the case of Tai Sang Wai, at the time of filming Voices from Elsewhere and Voices from Elsewhere we wondered if it was a special case. As it stands, the village as it stands is a replacement site for the original village, so supposedly it wouldn’t be demolished. But that’s just what was discussed, and if those in power want to demolish the village then they can. It seems like we cannot avoid these suburban developments, and the feeling is that it’s just a matter of when it is your turn. This issue is one of the reasons I started farming, but it has also created an opportunity for others to understand the situation.

What I mean to say with Voices from Nowhere is that from a modest starting point, such as understanding a fish, its internal world, and thoughts on survival, you can thus develop a multifaceted perspective towards how its ecological conditions can and do change. What I see now is a kind of stimulation for my work, as the fish of Tai Sang Wai face another challenge. The work is actually unfinished. What is tragic is that its world has to be so unstable.

Denny Demin Gallery Hong Kong

The Wild and The Tame

Exhibition Period: 11 June – 3 September 2022

Artists: Jessie Edelman, L , Natalie Lo Lai Lai, Dana Sherwood, Greer Howland Smith, Paula Wilson

Writers: Harmony Chan, Hayley Wu

Essay

Rossi & Rossi

A Collection in Two Acts

Exhibition Period: 16 July – 16 September 2022

Curated by Chris Wan | From the collection of Yuri van der Leest

Writer: Harmony Chan

A Collection in Two Acts

A Collection in Two Acts opens on July 16 through September 16 at Rossi & Rossi Hong Kong. Curated by Chris Wan, the exhibition utilises the private collection of Yuri van der Leest to present two frameworks of collectorship: one is institutional, such as museums and archives — treating artworks as files to be dealt with under a given context of art history; the other is personal, a private collection built with artworks as repositories of memories and personal encounters. Through the use of critical fabulation, the two modes of art collecting are juxtaposed to raise question about the structure and agency in the art system.

Writer – Harmony Chan

(Connected via HKAGA Summer Programme 2022 Open Call)

Graduating from Chinese University of Hong Kong with background in Cultural Management and Art, she worked in the art industry like many of the others. Seven years serving as an art docent, enlightened her passion for art interpretation. While many thinks that docent is a retired leisure, she believes interpretation, discussion and sharing are crucial parts in the habitat which is lacking of. The pandemic hit motivated the start of the new journey in art writing, using words on paper, instead of verbally, to continue the conversation between artists and audiences. Participated in Hong Kong Visual Art Critic Nurturing Programme. Her writings have been published on The Stand News, 1a space and CINEZEN, The Liminal Review, Rulerless and Fringe of Colour.

For more details, please visit gallery’s website here.

Institutional Exhibitions and Usurping the Discourse

Harmony Chan

Rossi & Rossi Gallery opened A Collection in Two Acts in July, an exhibition which signals detachment and immersion simultaneously. It is challenging for the audience to enter the exhibition with standard expectations. There are still sparse descriptions in the first half of the show for the majority of viewers who relies heavily on textual guidance, but most viewers will find themselves lost amongst the domestic setting in the second half. Without an ostensible topic or a straightforward curatorial direction, the exhibition is naturally one that stirs confusion. That is not to say that the exhibition is bad, but simply, it is incorrect to view the exhibition with common assumption. A Collection in Two Acts is neither constructed for the appreciation of artworks, nor guided by senses and sentiments. The artworks in this exhibition are treated as materials for the curatorial practice in framing the two acts. Instead of an exhibition, it might be more appropriate to comprehend it as a theatre set uninhabited by actors or two immersive installations.

The first act is set in a white cube. Sided by a small caption card, artworks are installed according to their date of creation on the white wall under white lights and a white ceiling. Standardised, like most gallery exhibitions in the city. Each work has their own space to be viewed independently. Most works on view are renowned artists in Hong Kong, and they each have outstanding features of their own. Yet, there is not much association between the works and artists besides the fact that some works are inspired by the scenery of Hong Kong. Even though the curatorial direction is not apparent, following a chronological order, we can faintly recognise the trend of art creation being influenced by social happenings: themes related to quarantine and staying at home are more recurrent after 2019. Here, the role of collectors is latent.

At the other end of the narrow hallway, visitors will find another exhibitions hall. The second act imitates that of a homely environment. Dimly lit, a projector sits a top of a coffee table in front of a sofa. Artworks of different sizes and genres cluttered on surrounding walls, looking disarrayed with works above and below each other. The works, from the left to right, are actually arranged according to the time of acquisition. The display reveals the collecting journey and preference of the collector; from the dense and crowded cityscape in Elephants in Hong Kong, to the anti-National Security Law protests documented in Gaze, these are all works reflecting his imagination of Hong Kong. As he makes Hong Kong home, his understanding of the city grows deeper and softer. This corner of the exhibition deliberately emulates the mood of a collector’s living room, that is warm, and feels like a lived space. Amongst works by mature artists are small paintings of the collector’s cats and a landscape painting done by Yuri’s mother. The coffee table does come from Yuri’s home. Taking quick glances around, we see everyday objects like a dishwashing sponge with YEP YEP printed on it, or Band-Aids with graphics by Yoshitomo Nara. It does not take much effort to imagine this collector as a homebody who likes to be close to his family and remains a child at heart. Details as such spread throughout the exhibition, providing clues for viewers’ imagination of the collector.

The two halls also take careful approaches in the documentation of information. To supplement the main narrative of the collection and the curation, the curator invited artists and the collector to write about the works on view. In the white cube, artists’ writings on their practices are compiled in files and kept in a cold metal file rack, like important documents that are about to be brought into an operation room. Over at the other side, the collector’s home offers descriptions written by the collector. Yuri writes in a more casual flow, encompassing any topic that comes to mind, such as his thoughts on the work, and his encounter with the artist. Instead of displaying these entries in a file, the writings are collected in a collage book, reminding viewers of a photo album or memorial book.

The interesting thing about this exhibition is that the audience has to immerse in order to detach. Meaning that the viewer must first accept that there are two “exhibitions within an exhibition”, immersing in each act as their own, reading all the details. Only then, can the viewer realise that this exhibition is trying to emulate the coming-to-be of an art exhibition (from a private collection to an institutional presentation), and to reflect on the narrative power of curation. This is a conscious reproduction that draws distance between the viewer and the art system, leaving space for contemplation. Quoting esteemed performance artist Tehching Hsieh, “The subject can experience, understand, and finally usurp the forces that bind it through deliberate and proven means.” The subject can reenact the forces that bind it through deliberate and proven means, and by doing so, experience, understand and finally usurp these forces.

Via minute details, the binary exhibition halls continue to show two ways of representation in and outside of the white cube. Although the collector persona in the show is known to be fabulation and intended to propel imagination, it is still fleshed out with details. The more character that the domestic setting puts on, the more visible that the white cube is wiping off the presence of a collector. Of course, this is not an issue of the white cube. The intention of the white cube is to erase any impact from the environment, allowing the audience to focus on the work itself. We have to be conscious of such deficiency. Collecting is not only a consumptive behavior, it reflects the preference and experience of a person, just as Yuri’s collection embodies his understanding to a place. However, moving from a private space to a venue open to public, the voice of individuals are completely overshadowed through institutionalised exhibition. Even though museums often name exhibition halls after contributing collectors, it does not make it easier for viewers to understand what the collector thinks. As the viewer come to this realisation, they will notice that there are myriad of individual voices that have been neglected in the ecosystem of art – those of collectors, artists, and even audience.

This explains why the curator invited the artists and collector to elaborate textually, adding to the narrative in varying perspectives. Yet, this is an endless cycle. Once you decide to include a certain voice, you make the choice to rid another voice; you notice the lack of a voice, and you patch it, then you notice the absence of another voice – and the process occurs all over again. Exhibitions are unable to restore all voices of the world, because curation and archiving are practices of selection and focus. Even though individual voices end up as fragments of the world’s grand narrative, curator Chris Wan Feng believes that individual accounts still matter. Confronting the constant paradox of addition and absence, the crucial point is not to complete the narrative; instead, it is to be constantly aware of the reality where individual voices are overpowered in the art system. Upholding this mentality enables the act of understanding and usurping, as Tehching Hsieh proposed. As we usurp the narrative power of institutions, we keep the diversity in narration.